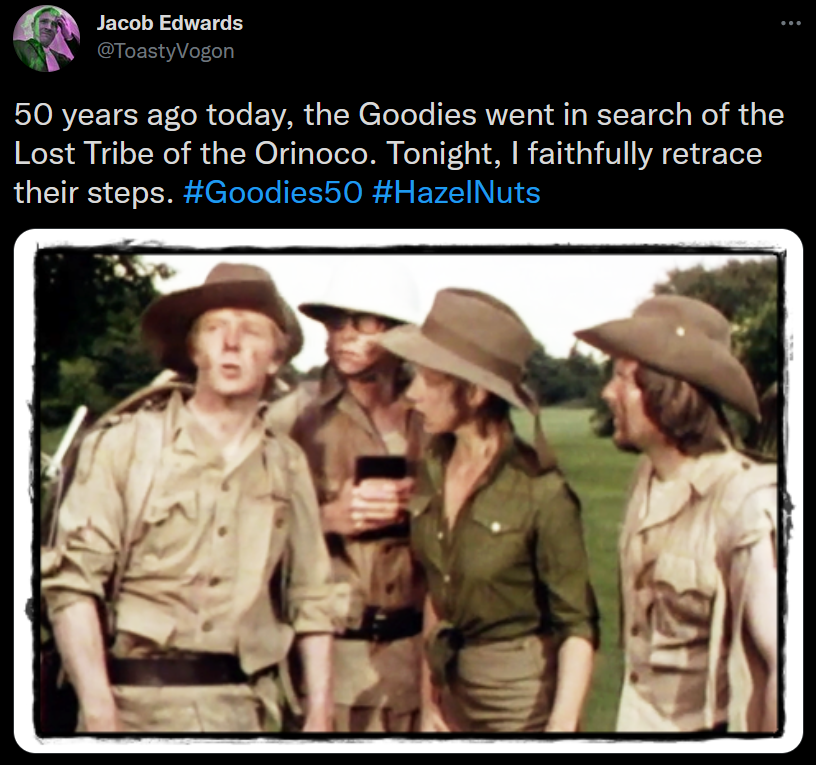

The Lost Tribe

22 October 1971

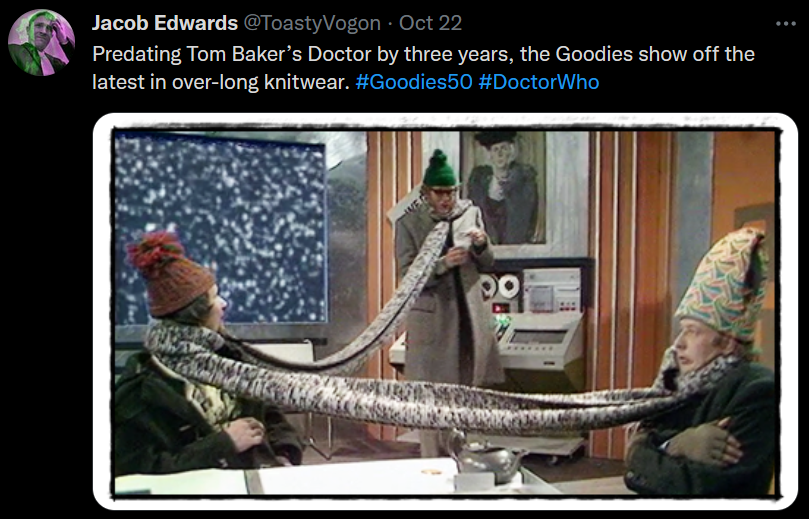

The Goodies are cold: teeth chatteringly, tea cosy–wearingly cold. Graeme has spurned traditional methods of office heating in favour of a nuclear generator, which they can’t afford to run, and Tim’s nice hot cup of tea has just snap-frozen. Miserable and impecunious, the lads resolve not to take any more charity cases…

Then Hazel arrives.

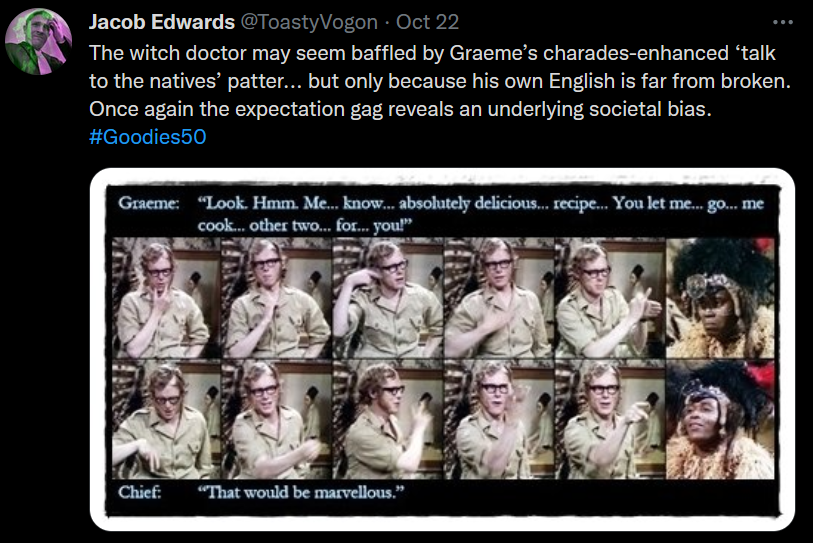

And so begins the Goodies’ search for the Lost Tribe of the Orinoco—one of their less remarkable undertakings, though amusing enough in the small details. Moving on from the seriousness of ‘Pollution’, the lads revert to visual humour, expectation gags and the tried-and-true staple of getting up / falling down. Additionally, the tent scenes give us an early taste of what would become the lads’ trademark ‘confinement comedy’.

The Goodies soon showed themselves masters of making jokes from nothing. At the height of their powers, this facility served to flesh out and elevate plots already brimming with inspiration. In lesser stories—such as this one—it papers over the lack of substance. (That said, the Goodies’ wallpaper is still the zaniest in town!)

There’s nothing uproarious in ‘The Lost Tribe’ but the outdoor scenes do float along nicely, set to the pseudo-instrumental Travelling Theme and then the more socially droll Away From It All. This latter composition (“I’d really like to live in the country, if it wasn’t so far away”) encapsulates one of the story’s underlying ideas: a low-key ridiculing of those who would romanticise far-off places and adventures but never participate in anything that might inconvenience their city lifestyle. The episode also makes a point of time’s propensity for moving on. When the Goodies set out to re-create Professor Nuts’ expedition of twenty years’ previous, they end up hacking with machetes alongside the motorway!

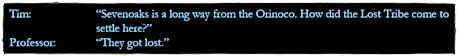

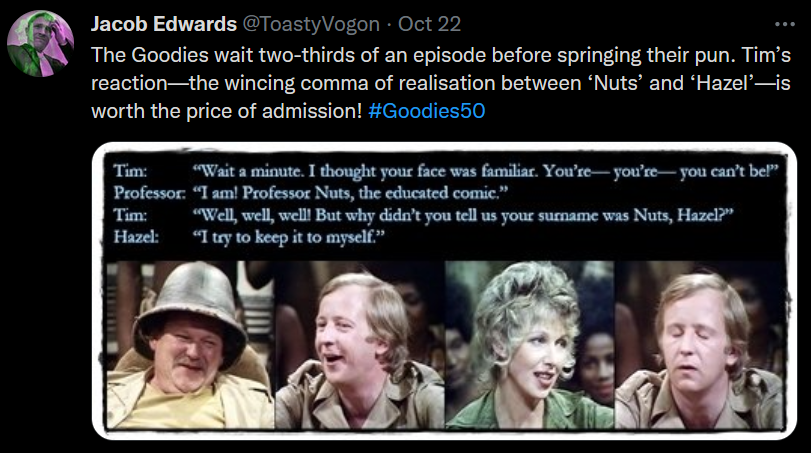

Beneath its superficial absurdities, ‘The Lost Tribe’ contains a curious interplay of ideas. Professor Nuts (played by Roy Kinnear) turns out not to be an anthropologist or even much of an explorer, but rather a (sitting down) stand-up comic whose jokes are so tired, he doesn’t give them more than a perfunctory delivery and a raise of his pith helmet.

The Professor may once have been at the forefront of comedy. Time, however, has overtaken him. (In the words of his last diary entry: “I have mysteriously disappeared without trace.”) Moreover, it has shown him up as been not-so-adventurous to begin with. Yes, he found the Lost Tribe (“They were the only people in the world who hadn’t heard my jokes”), but he found them in Sevenoaks, Kent, not the far-off Orinoco! And the Professor stayed. He got comfortable with an audience that appreciated him no matter what.[1] He lost his comedic edge.

By following in his footsteps the Goodies can only lose theirs in turn.

The other issue that comes into play in ‘The Lost Tribe’ is that of women in comedy. Granted, this might be an over-interpretation the text. Hazel could be a foil, nothing more. A plot device. But what if we read beneath this surface impression? Following in her father’s footsteps, what can Hazel (played by New Zealand actress Bridget Armstrong) tell us about females in what was, and to an extent still is, a male-dominated industry?

Hazel is attractive. This gets her in the door, yet is then held against her. (The Goodies would do anything for their new client but Tim in particular refuses to believe she won’t be a hinderance.) She comes across as ditzy in an upper class kind of way, the laughs coming from her lack of awareness. But which is the act: hers or her ‘cheery commoner’ dad’s? Hazel certainly has the better delivery. Her account of how her father went missing—for twenty years without her noticing!—is perfectly pitched to let the farcical nature speak for itself. And what of Hazel’s competence? Yes, it’s a good joke when, having been left behind, she catches a London bus to join the Goodies at their motorway campsite. But logistically, this means she must have memorised her dad’s diary (which she’d only recently received) and calculated where and when the lads would end up should they follow it. She is, beneath the persona inflicted upon her, clearly sharper than the males of the story.

So, why did Hazel come to the Goodies for help? And why in the end does she stay with her father? Is this a veiled commentary on female disempowerment? A couched call to arms for women to stand up and fight for their rightful place on stage?

Or is Hazel just inconsistently written—an all-purpose catalyst for the lads’ tomfoolery? In truth, given the Goodies’ almost total indifference to continuity, this does seem more likely!

And yet…

Ideas in The Goodies tend to make their appearance in nascent form and then resurface in later episodes. Take Professor Nuts’ jungle drums, for instance (a gag played to better effect in ‘South Africa’), or the somewhat untethered rendition of ‘Crest of a Wave’ (the same scouting song so brilliantly played in ‘Scoutrageous’). The Goodies would subsequently give us Mildred Makepeace and Caroline Kook, two powerhouses of feminist enfranchisement. Could it be that these fan favourites had their origins in Hazel Nuts?

If we take ‘The Lost Tribe’ as demonstrating the need for reinvention, anything seems possible.

Jacob Edwards, 22 October 2021

Tweets:

[1] Compare this with John Cleese, who reportedly would become frustrated—even angry—when studio audiences of radio programme I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again laughed uncritically at material that he himself found substandard.

Previous: Pollution

Next: The Music Lovers