Culture for the Masses

5 November 1971

‘The Music Lovers’, it transpires, was merely the take-off step before jumping. Live performances may have been under threat due to the rising preponderance of discothèques, yet music was already an artform of wide popular appeal. It defined and expressed the culture of the 60s and 70s, purists be damned.

But what of art?

‘Culture for the Masses’ is a gloriously cynical, absurdly funny lampoon of pretentiousness and snobbery (both at an individual level and on a national scale). It takes the notion of artistic merit and, with a subtlety belied by the lads’ antics, forces us to consider and reconsider our values. The critique is brilliantly executed, resplendent with comedic flourishes. We’re so busy laughing, it’s only with hindsight that we can appreciate what’s being said.

Tim is the standout viewpoint character, an English patriot whose notions of fine art are tied less to any intrinsic appreciation than to his high-minded conception of self and country. It is Tim who insists on denying the Velázquez to foreign buyers (“Those aren’t art lovers; they’re Americans!”) and having it hung instead in the National Gallery—at any cost! It is Tim who then decrees that art should be free for the people to enjoy, even if those people never come to view it. It is Tim who, prior to giving the Velázquez to the nation (along with the bill!), hangs it on the office wall (still upside-down!) behind its own protective curtain, and even kisses the canvas—but not because he actually likes the painting. Tim sees the purchase as a national triumph; as vindication of his own identity:

Beyond this notional ideal, Tim himself has no deep reverence for art. His treatment of the various gallery pieces during the Goodies’ outrageous spring cleaning (to the Renaissance fusion instrumental ‘Travelling Theme’) is enough to leave a genuine connoisseur comatose from shock. Eventually, he recognises the folly of his stance, and resolves to part ways with the world’s most expensive masterpiece.

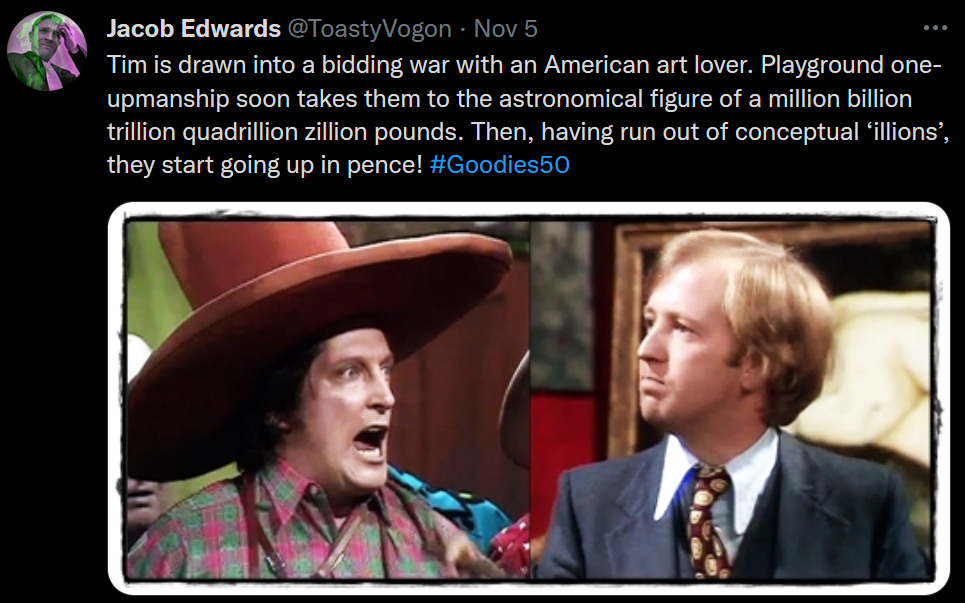

Tim, of course, isn’t the only person making a show of artistic appreciation. Yes, there are the Americans in their 10-gallon hats, who wolf-whistle the Velázquez (having previously shown themselves willing to spend great wads of cash on a painting they haven’t even seen). But they are just the most blatant in seeking out art as a measure of status—and really, is their coveting any different from Tim’s? There’s also the Auctioneer (Tommy Godfrey), who has hung the painting upside-down and has no conception of how to pronounce ‘Velázquez’; and the Minister of Culture (Julian Orchard), who meets Tim’s idealism with irritated sufferance, and whose reaction when first presented with the Velázquez is, “Oh yes. What is it? Did you do it?”

The general lack of interest in art, or veneration for it, extends to Tim’s fellow Goodies. When Tim starts advocating for the Velázquez to remain on home soil, the others are unenthused (even if Graeme has brought his saxophone in readiness!).

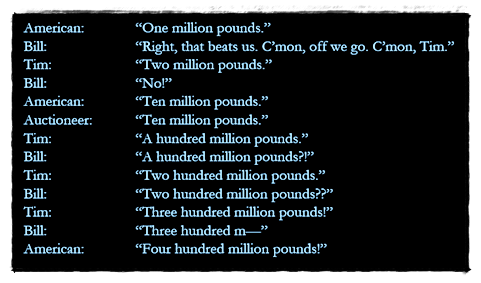

When Tim starts bidding on the Velázquez, Bill’s panicked incredulity serves only to make matters worse:

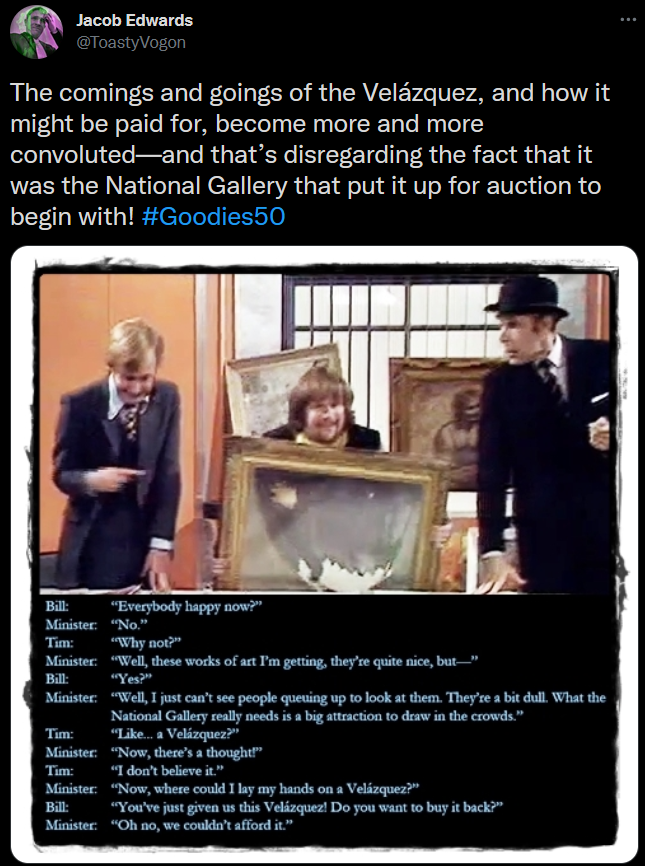

When Tim wins out in the auction, Bill and Graeme’s instinctive cheering gives way quickly to dismay. (Bill: “What are we cheering for?” Graeme: “I dunno.” Bill/Graeme: “What have you done, you fool?”) And when the Minister seeks a cross-section of public opinion, Tim is fervently in favour of the Velázquez but the other two vote against it. (Tim: “Traitors!” Minister: “There you go. You see, two out of three British people don’t want it.”)

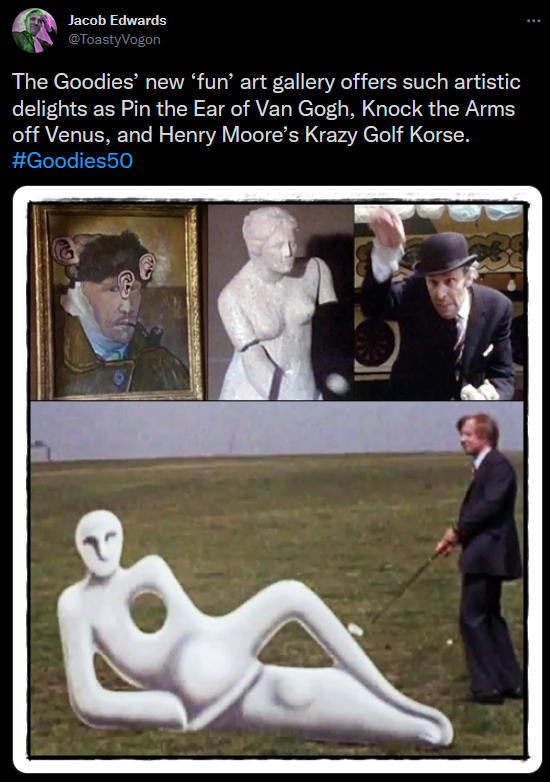

The crux of the matter is that Tim’s determination stems purely from patriotism. In the absence of this in its extreme form, and lacking any personal connection to the artworks in question, no-one else cares a jot what does or does not hang in the National Gallery. It is little wonder, then, that the Goodies’ fun-fair styled art gallery takes off (to the sublime musical strains of ‘Fun Palace’) and becomes profitable enough to buy back all the original pieces that the Goodies stole (so as to activate the insurance policy and allow the Gallery to buy back the Velázquez). Not that anyone wants these now.

And this seems to be the moral of the story. In the end, people should be more like Bill (!) and value what they enjoy, not what they’re told is good or what fits some abstract notion of quality. (And yes, this is the same Bill who looks down on old paintings for being second-hand; who would spurn a Renoir nude in favour of a lifetime’s subscription to Playboy; and who ultimately, like Tim but from more personal motives, refuses to part with his print of ‘Monarch of the Glen’—at any price![1]) Even the Americans come to their senses and lose their interest in buying paintings they don’t like the look of.

Throw away the trappings. Purge yourself of pretentiousness. Cast off your inhibitions and immerse yourself fully in what actually makes you happy.

It’s an easy idea to get behind when watching The Goodies!

Jacob Edwards, 5 November 2021

Tweets:

[1] Aptly enough, this much-reproduced painting (truly, culture for the masses) was in 2017 acquired for £4 million and now hangs in the Scottish National Gallery.

Previous: The Music Lovers

Next: Kitten Kong